Since the Dark Ages, Jewish communities across Europe have faced unprecedented atrocities marked by expulsion, forced isolation, and systematic exclusion. England, France, Spain, Portugal, and Germany had expelled their Jewish populations or confined them to ghettos. During those challenging times, Jews were invited back, but often with strict limitations on their livelihoods. Many were denied the right to own property, and their professions were restricted in some places.

One of the few professions in which Jews were permitted to try their luck was moneylending. This was a job that Christians were forbidden to undertake due to the church’s strict laws on usury, which prohibited charging interest on loans. For Jewish communities, however, moneylending became a lifeline—a profession synonymous with survival during times of severe restrictions. Over time, this seemingly modest and marginalized occupation evolved into the foundation of modern banking. Families like the Rothschilds emerged as trailblazers, establishing some of the earliest banking institutions in Europe. What initially started as a desperate means of survival eventually grew into a transformative opportunity that reshaped financial systems and opened doors to uncharted possibilities.

In addition to banking, Jews faced countless barriers to owning land or businesses, leaving them with few avenues to build livelihoods. Despite these limitations, they carved out a niche in managing capital. Those who succeeded in this line of work not only secured their survival but also provided a better future for their families, often breaking the cycle of poverty that had plagued their communities for generations.

However, not all Jews pursued careers in finance. Many took on the roles of tradespeople, becoming merchants or artisans who traveled from town to town offering goods and services. As Jewish populations expanded across Eastern Europe, settling in regions like Poland, Russia, and Czechoslovakia, they adapted to their new environments by establishing farms, businesses, and various trades. These efforts helped create thriving communities, laying the groundwork for economic stability and cultural resilience amidst challenging circumstances.

America: The Land of Opportunities

When Jews were forced to leave Europe, many found new opportunities in America. As the country expanded, Jewish communities followed, moving from large cities to smaller towns. However, even in the United States, Jewish merchants faced resistance. Their observance of Shabbat—closing their shops on Saturdays and opening on Sundays—clashed with local customs, especially in the South, where many towns observed strict Sunday “blue laws” that restricted business.

Over time, these blue laws faded, particularly in areas where Jewish populations grew, and their work ethic and family values flourished.

A famous example of Jewish success in America is Levi Strauss, who traveled west with a wagon of goods, hoping to sell to the gold miners of California. They needed durable pants for long hours of labor in the mines. Levi first made pants from canvas but later switched to denim. Thus, the first pair of jeans was born. Over time, they became a staple for miners, cowboys, and construction workers and, eventually, a fashion staple worldwide.

Coming from Europe, where opportunities were limited, Jewish families in America were determined to make the most of what they could.

The Power of Primogeniture: A Tradition of Inherited Success

One of the less discussed but highly impactful reasons for Jewish business success is the tradition of primogeniture—where the family business is passed down to the eldest child. This practice has played a significant role in preserving and growing Jewish family businesses across generations.

In many cultures, the death of a founder means the end of the business, but in Jewish tradition, it is the opposite. The eldest child is often trained from a young age to take over, so the legacy continues.

This process ensures that wealth and resources are not divided and the business remains unified. It also encourages long-term planning, family unity, and future prosperity. For generations, Jewish families have successfully maintained their businesses, influence, and economic strength through primogeniture.

Resilience and Adaptation: Keys to Jewish Success

Jewish success is not a product of chance but of resilience, adaptability, and a deep sense of responsibility toward family and community.

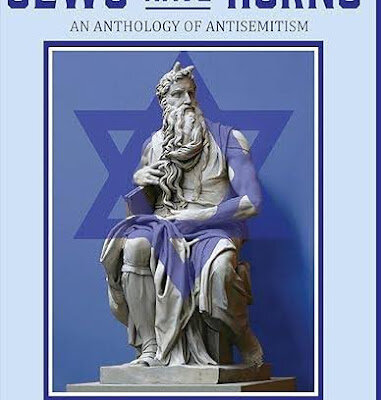

Jews Have Horns: An Anthology of Antisemitism by Wilbur and Sara Pierce explores Jewish history thoroughly. The book details personal stories and historical accounts to explore how Jews survived and thrived in a world that dehumanized and discriminated against them.

In recounting these stories, the book emphasizes how antisemitism shaped Jewish identity and contributed to a strong sense of community. These stories remind us that Jewish success is not simply about wealth or business acumen—it’s about a community that has, time and again, overcome adversity and emerged stronger, preserving a legacy of success for future generations.

Get your copy of Jews Have Horns: An Anthology of Antisemitism by Wilbur and Sara Pierce now. The book is available on Amazon.